The Autonomous Workforce of the Nation:

A National Time-Bank Strategy for the United States

From Layoffs to Labor Scarcity: A Post-2025 Reckoning · by Uwe Jens Cerron

Dedicated to the builders, engineers, operators, and technicians turning energy into capability. Those who create something out of nothing. To Marc Raibert.

Loading embed…

View on X"America cannot loose the robotics race with China." , Martin Casado, A16z

The United States is experiencing a stark whiplash in its labor market. In 2025, mass layoffs have surged to levels not seen since the Great Recession , over 1.09 million job cuts were announced in the first ten months of the year, a 65% jump from 20241. Companies across tech, retail, and logistics are aggressively "right-sizing" their payrolls, often citing cost-cutting and accelerated adoption of AI automation as justification2. Warehousing alone saw a 378% year-on-year increase in layoffs as automated systems displaced roles once considered secure3. This wave of redundancies has loosened the once-tight labor market, making it harder for displaced workers to find new roles4.

Yet, paradoxically, behind this glut of job cuts lies an underlying scarcity of labor. The Great Resignation of 2021,2022 marked an exodus of workers from the labor force, a trend only partially reversed. By mid-2024, U.S. workforce participation remained 1.7 million workers below its pre-pandemic level5. Early retirements surged and younger cohorts showed reluctance to fill the gap. Immigration , the historical remedy for U.S. labor shortfalls , has also fallen short. Pandemic-era travel restrictions and stricter immigration sentiment led to a shortage of migrant workers, exacerbating vacancies in critical industries6. In the past, high immigration helped counterbalance aging demographics, but in recent years a decrease in immigration has removed a large portion of the potential working-age population7. Even as enforcement priorities shift (with ICE now focused on deporting serious criminals), net labor inflows remain subdued. The result is a structurally tightening labor pool, especially in skilled trades and caregiving roles that cannot easily be outsourced.

Demographics are the ultimate driver. The nation is aging into a chronic worker deficit. The population over 65 is growing nearly five times faster than the working-age population. Baby boomers are retiring in record numbers, while birth rates remain below replacement levels. This is not a cyclical downturn; it is a permanent labor scarcity. As one analysis notes, "an aging population and a labor shortage accelerate industrial automation." When human labor is scarce, machines will step in to fill the void. The solution is clear: expanding the nation's productive hours through automation.8,9

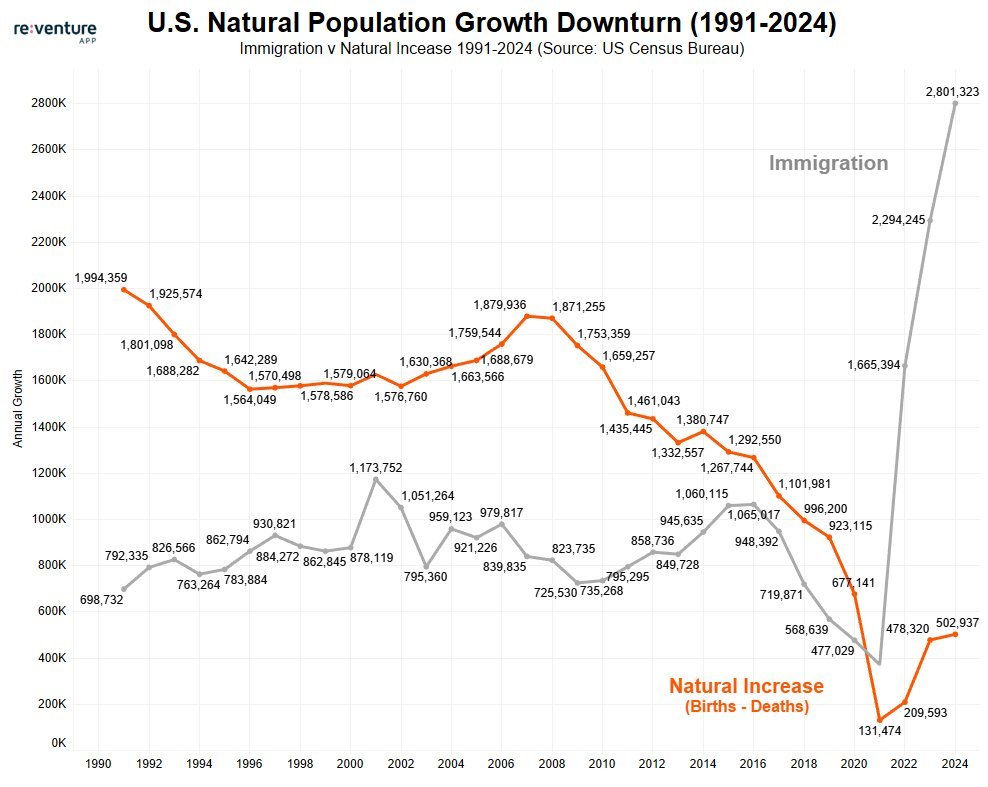

Source: U.S. Census / vital statistics (natural increase) and immigration estimates. Why it matters: U.S. natural population growth (births minus deaths) has declined from 1.99 million in 1991 to just 131,474 in 2021, recovering slightly to 502,937 by 2024. Immigration has surged from 698,732 in 1991 to 2.8 million by 2024, becoming the dominant driver of population growth. The lines crossed around 2019–2020: America now depends on immigration to maintain population growth as natural increase collapses—the labor-scarcity backdrop for the AWN strategy.

Against this backdrop, U.S. policymakers and technologists are converging on a bold strategy. Rather than viewing automation as a threat to American workers, it can be reframed as augmenting the national workforce. The goal is not merely to boost corporate productivity, but to establish a National reserve of robotic labor a "time-bank" of machine work hours that the nation can draw on to stabilize the economy. By actively investing in robotics and AI-enabled autonomy, the United States can build an Autonomous Workforce of the Nation (AWN): an aggregated workforce of robots and automated systems that complements and underpins human labor. This essay lays out that strategy. It explains the metrics and mechanics of a national autonomous workforce, quantifies the economic framework (from robot capital costs to labor substitution rates and energy constraints), and explores how a "National Time Dividend" could pay out to every citizen in the form of greater prosperity and lower cost of living. The analysis proceeds as a narrative, weaving together current trends and forward-looking models into a cohesive policy vision.

The Autonomous Workforce of the Nation: Defining a National Labor Stock

At the heart of this strategy is a simple but powerful idea: measure a nation's strength not just in dollars of GDP or number of workers, but in total available work-hours (human + machine). We introduce a metric to formalize this: the National Autonomous Work Index (NAWI), which we will refer to narratively as the Autonomous Workforce of the Nation (AWN). In essence, NAWI quantifies the total annual hours of productive work that can be performed by robots and automated systems within the economy. Just as we count human labor hours, we must count autonomous hours. Formally, one can define the autonomous workforce capacity at any time t as:

Variable definitions:

- NAWIt (National Autonomous Work Index): The aggregate metric representing a nation’s total machine labor capacity at a specific time (t). It translates various forms of automation into a standardized “full-time equivalent” work-hour contribution to the national economy.

- Ni,t (Robot Stock): The total number of operational robots or autonomous units of a specific type (i) available in the workforce at time t.

- hi,t (Utilization Hours): The average number of hours per year that each robot of type i is actively utilized for productive tasks.

- φi,t (Task Substitution Factor): A coefficient reflecting the technical effectiveness of the robot compared to a human worker. Values typically range from 0.5 (for specialized, limited-task bots like warehouse arms) to 1.0 (for advanced, general-purpose humanoids capable of full human-task parity).

- i (Type Index): Represents the specific category or class of automation being measured (e.g., software agents, industrial robots, or humanoid platforms).

- n (Total Categories): The total number of different types of autonomous systems included in the national aggregation.

- t (Time): The specific year or period for which the index is being calculated.

Summing N × h × φ across all robot types yields the total effective robotic work-hours available per year—an index of the nation’s machine labor capacity11. For example, a basic warehouse robot might have φ ≈ 0.5 (able to do half the tasks a human could per hour), whereas an advanced autonomous vehicle or humanoid might approach φ ≈ 1.0 or higher in specific tasks.

Crucially, this metric is additive and composable. It treats a fleet of 100 simple robots working 2,000 hours a year at 50% productivity (100 × 2,000 × 0.5 = 100,000 hours) as equivalent to 50 more capable robots working 2,000 hours at full productivity (50 × 2,000 × 1.0 = 100,000 hours). Both scenarios contribute 100,000 autonomous hours to AWN. In this way, AWN provides a common denominator for heterogeneous automation , from software bots to factory arms to general-purpose humanoids , translating all into "full-time equivalent" work-hour contributions. It is, in effect, a labor force headcount for machines, measured in hours.

This concept allows us to speak of the nation's robotic workforce in concrete terms. Today, the U.S. AWN is nascent , on the order of perhaps a few hundred million autonomous hours annually (mostly from industrial robots in factories). But with concerted investment, AWN could grow by orders of magnitude in the coming decade. We can imagine a future where the U.S. has, say, 1 million active robots each working ~6,000 hours/year (multiple shifts with high uptime) at an average φ of 0.8. That would yield AWN ≈ 4.8 billion hours , roughly equivalent to 2.5 million full-time human workers (assuming 2,000 hours per worker-year). In other words, the robot workforce could effectively "hire" millions of synthetic workers to bolster national productivity.

Framing automation in terms of an autonomous workforce has several advantages. First, it makes the policy goal explicit: increase AWN in a balanced way, similar to how we seek to grow employment or labor productivity. Second, it shifts the narrative from "robots stealing jobs" to "robots filling jobs we can't otherwise fill." Given demographic and immigration constraints, the U.S. will need these additional hours simply to sustain economic growth. The AWN metric lets policymakers track progress, much as unemployment or labor participation rates are tracked. It could be published by agencies (e.g. a National Robotics Council) to guide decision-making12,13. Finally, it underscores that robots are a complement to human labor at the macro scale , a reserve of hours that, if harnessed well, can increase overall economic capacity and resilience.

Loading embed…

View on X"The only cost is time." , Corbin Braun

A helpful analogy is to think in terms of a "Time Bank" for the nation14. Each robot added to the economy is like depositing capital that yields interest in the form of hours. The principal is the upfront investment (the cost to build and deploy the robot). The interest is the stream of tasks it performs autonomously thereafter. With each passing year, the "balance" of available autonomous hours in this time bank increases as more robots come online and existing ones become more capable. The liquidity of this time bank is determined by how flexibly those robot hours can be allocated to different tasks (for instance, a general-purpose humanoid offers more redeployable hours than a single-purpose machine). Just as a financial bank measures assets and interest, a national time bank would measure deposits of autonomous hours and the compound growth as robots replicate or get more efficient15,16. If properly managed, this time bank can yield exponential dividends: each hour of robot work today can, through reinvestment and learning-by-doing, lead to even more robot hours tomorrow , a virtuous cycle of embodied productivity growth.

In summary, the Autonomous Workforce of the Nation represents a National labor stock under U.S. control. It is the sum total of machine labor capacity that the country can deploy alongside its human workforce. Nations run on hours, not just dollars , and AWN is a way to ensure there are enough hours to go around. By elevating AWN growth to a strategic priority, the United States can directly address the labor shortfalls and volatility that define our current era. But growing this autonomous workforce is not as simple as flipping a switch; it requires careful consideration of economics, technology, and policy. We turn next to the economic framework underpinning a National robot workforce strategy , from the cost dynamics of robots themselves to the macroeconomic dividend of their output.

Humanoid Robotics Startups: The Emerging Landscape

The humanoid robotics sector is rapidly evolving, with multiple companies racing to develop general-purpose robots that can augment the national workforce. The following table provides an overview of key players in this space as of December 2025:

| Company | HQ | Valuation ($BN) | Market | Intel | Data | Hardware | Prod. Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIGURE | 🇺🇸 USA | 39 | 🏠 🏭 | In-house (Helix model) | Human-generated video (Project Go-Big) | In-house (BotQ facility) | 12k target (100k by 2029) |

| 1X | 🇺🇸 USA | 10 | 🏠 🏭 | In-house (Redwood model) | Teleop | In-house (facilities in USA & Norway) | ? |

| NEURA robotics | 🇩🇪 Germany | 9-11 | 🏭 | In-house | NEURAGym (real-world data) | In-house (key components) | ? |

| UBTECH | 🇨🇳 China | 8 (publicly traded) | 🏭 | Outsourced (partners with DeepSeek) | Teleop | In-house (2 facilities in China) | 5k target by 2026 |

| UNITREE | 🇨🇳 China | 7 (exp. market cap at IPO) | 🏭 | In-house (UnifoLM-WMA-0 model) | Teleop & human-generated video | In-house (facilities in China) | ~1k |

| RAINBOW ROBOTICS | 🇰🇷 South Korea | 7 (publicly traded) | 🏭 | In-house (partners with Samsung) | Teleop & simulation | In-house (facilities in South Korea) | <1k |

| [Unnamed] | 🇺🇸 USA | 6 | 🏭 | Outsourced (partners with Google & NVIDIA) | Teleop & simulation | In-house & outsourced (partners with Jabil) | ? |

| Physical Intelligence (π) | 🇺🇸 USA | 6 | 🏠 🏭 | In-house (π*0.6 model) | Teleop & RL | n.a. | n.a. |

This landscape demonstrates the global competition in humanoid robotics, with significant investments from the United States, China, Germany, and South Korea. The diversity in approaches , from in-house intelligence models to outsourced partnerships, from teleoperation to human-generated video data , reflects the early-stage nature of this industry. As these companies scale production capacity, they will collectively contribute to the growth of the Autonomous Workforce of the Nation, transforming the availability of productive hours across the economy.

The National Time Dividend: Harnessing Hours for Prosperity

Empowering an autonomous workforce at national scale is not an end in itself; the ultimate goal is to deliver broad-based benefits to society. The promise of automation must be translated into higher living standards , a National Time Dividend that improves everyday life. This dividend can be understood in two complementary ways:

Loading embed…

View on X1. Lower Cost of Living through Robot Productivity. As robots take on more production, they can drive down the real costs of goods and services, effectively "paying" the public through cheaper prices. If autonomous systems make construction cheaper, housing becomes more affordable. If robot farming and trucking cut food and freight costs, consumer prices fall. Unlike a one-time stimulus check, this dividend is ongoing , a structural reduction in the cost of living enabled by ultra-productive, low-cost labor. Importantly, this benefit does not rely on taxing or redistributing someone else's income; it is a wealth created by new autonomous output. For example, imagine humanoid robots in manufacturing reduce the cost of domestic-made appliances by 30% over a decade. Every American household would feel that gain in their pocketbook. In essence, the output of the robot workforce is shared with consumers via market prices, increasing real purchasing power. This approach aligns with free-market principles (hence appealing to a fiscally conservative viewpoint): instead of establishing new entitlements, policy would focus on fostering competition and diffusion of automation so that savings are passed on widely. One could consider this a form of "robot dividend" , analogous to a resource dividend in an oil-rich state, but here the resource is productive hours. The more autonomous hours in the economy, the more abundance and deflationary pressure on prices of essentials.

2. Time Back to Citizens (Leisure and Work-Life Balance). Another form of the dividend is in time saved for people. If robots can do in 30 hours what used to take a human 40 hours, that's 10 hours returned to the person , potentially to spend with family, in education, or in higher-value creative work. A nation could see average work weeks gradually fall (say from 40 to 30 hours) while maintaining or even increasing output. Importantly, this time dividend often doesn't show up in GDP statistics17 , GDP counts output, not leisure. But from a quality-of-life perspective, it is immensely valuable. In the early 20th century, rising productivity yielded the weekend; in the 21st, autonomous productivity could yield a shorter workweek or more flexible careers. For policy makers, the challenge is ensuring that the benefits of robotic productivity do translate into either lower prices or shorter hours, rather than being captured entirely as corporate profit. This might entail encouraging competitive markets (to pass on cost savings) and supporting labor arrangements that trade some productivity gains for reduced hours without pay loss. The national time dividend thus has a dual meaning: cheaper goods and more free time , both stemming from the bounty of autonomous labor.

It's worth noting that these outcomes are not automatic. They require what one might call a Turing-era social contract: the gains from AI and robotics must be reinvested in workers and consumers. This could involve novel mechanisms. For instance, some economists propose a National robotics fund that owns shares in robot-producing firms or takes equity stakes in automation projects, using the returns to pay out a social dividend. Others suggest tax incentives for companies that demonstrably lower prices via automation or that implement work-share policies when introducing robots (so employees work fewer hours for the same pay rather than lose jobs). A more indirect but effective approach is simply scaling the technology as widely as possible , an abundant supply of robot labor will inherently push down its "wage" (i.e. the service price of automated labor), benefiting all users of that labor. In any case, the policy ethos is clear: treat autonomous labor as a public utility-like boon to be maximized and broadly shared, not a private productivity secret to be hoarded. Done right, every additional percentage point of AWN growth could translate into tangible relief for households , cheaper groceries, cheaper rent, or an extra hour at home in the evening.

Finally, consider national resilience. In crises , whether pandemics, wars, or natural disasters , having a large autonomous workforce to draw upon can be a societal lifeline. Automated supply chains can keep food and medicine flowing when human labor is disrupted. Recovery and rebuilding can be accelerated by robotic crews working around the clock. In this sense, the autonomous workforce is also a strategic reserve. Just as the U.S. maintains a Strategic Petroleum Reserve for energy security, building up an "Autonomous Time Reserve" strengthens labor security. It insures the nation against labor shocks and enhances Nationalty: we become less dependent on foreign labor or vulnerable supply chains if we can internally deploy fleets of robots to meet demand surges. This has a geopolitical dimension too , as other countries (notably China) race to develop massive robot labor capacity, America must not fall behind in the quantity or quality of autonomous hours at its disposal18,19. The nation that best harnesses AI-driven robotics will enjoy not only economic advantages but also greater freedom of action in the global arena. In summary, the national time-bank strategy is about converting technological gains into time and prosperity for the American people. It asserts that by treating hours as wealth, and growing that wealth through machines, we can achieve both economic dynamism and a renewal of the American Dream in the form of less grind and more grace in everyday life.

Displacement and Transition: Managing the Shock of Automation

Loading embed…

View on XNo discussion of a sweeping automation strategy is complete without addressing the elephant in the room: worker displacement. As robots assume a larger share of tasks, what happens to the human workers performing those tasks today? The transition must be managed to avoid severe social dislocation. We need to quantify the rate at which human labor can be safely displaced or redeployed, and design policy to keep the process within those bounds.

A starting point is the displacement rate equation. We can express the annual rate of human job displacement (D_t) due to automation as a function of AWN growth:

where ΔAWN_t is the increase in autonomous work-hours per year (the growth of robot labor), and Ω (Omega) is the task overlap coefficient , the fraction of those new robot hours that directly substitute for tasks humans are currently doing. If robots are mostly performing entirely new functions, Ω would be low and displacement minimal. If they are predominantly doing work identical to humans, Ω approaches 1, and each robot hour potentially displaces a human hour. In practice, Ω might vary by sector: a robotic packer in a warehouse has a high task overlap with human packers, whereas an AI that monitors machine data might be doing a task no human formally did before (low overlap, more complementary).

Even when Ω is high, not every displaced hour translates to an unemployed worker; some human labor will shift to other roles. This is where the concept of displacement elasticity (σ) comes in. σ measures the economy's ability to absorb or reallocate workers in response to automation. If σ = 0, every automated hour purely replaces a human hour (one-for-one job loss in the short run). If σ > 0, the economy creates new demand for labor in response to productivity gains , e.g. lower prices stimulate higher demand, requiring more human workers elsewhere, or new job categories emerge alongside the machines. Empirically, σ is not zero , historically, technology has displaced certain jobs but created others (from ATMs displacing some bank tellers but fueling new banking services, to software automating clerical work but spawning the IT industry). However, σ is not 1 either , transitions take time, and frictions exist (skills mismatches, geographic immobility, etc.).

Policymakers thus face a balancing act: pace the automation such that displacement stays within the economy's absorption capacity. One useful benchmark is the natural attrition rate of the labor force , roughly the rate of retirements and voluntary exits. In the U.S., about 2,3% of workers retire or leave the workforce annually. This suggests that if automated labor grows equivalent to (say) 3% of human labor per year, it can theoretically be absorbed largely by retirements and a slowdown in hiring, rather than mass layoffs. But if it accelerates to, say, 10% of human labor per year, the "shock" could exceed what retraining and new job creation can accommodate in the short term.

In concrete terms, consider an economy with 150 million workers. A 3% net displacement would affect ~4.5 million workers a year , which is around the scale of monthly job turnover in the U.S. (hires and quits) spread over a year, arguably manageable with aggressive retraining and natural churn. But a 10% displacement would mean ~15 million workers needing new jobs in a year , an upheaval roughly akin to the spring 2020 pandemic layoffs, and deeply destabilizing if repeated year after year.

Thus, the trajectory of AWN must be smoothed to prevent acute shocks. This does not necessarily mean slowing technological progress; rather it may mean policy measures to stretch out and synchronize the adoption curve with workforce transition programs. For example, if a revolutionary warehouse robot is ready to deploy, incentives could be structured to phase it in over 5,7 years instead of 2,3, giving human workers time to retire or retrain. Displacement elasticity can be improved (made more positive) by robust investments in education, apprenticeship, and geographic mobility , so that freed-up workers more readily move into emerging jobs (for instance, technicians to maintain robots, or service roles that machines can't do). Additionally, shock absorbers like wage insurance, earned income tax credits, or even temporary universal basic income (UBI) stipends can cushion displaced workers during the transition. These should be seen as integral components of a Turing strategy; they ensure the robotic dividend is not paid in unemployment checks.

It's also crucial to highlight which sectors and communities will be most affected. Early waves of automation hit manufacturing; now AI is encroaching on some white-collar work (e.g. AI assistants for coding, writing, customer service). The coming autonomous workforce will extend into logistics, retail, food service, and beyond. Policymakers can map the exposure: e.g., how many truck drivers, warehouse pickers, or fast-food cooks might be phased out under various AWN growth scenarios. With that, targeted transition plans (like scholarships for younger workers in those fields to move into healthcare or robotics maintenance) can be implemented. We might, for instance, estimate that a 5x increase in warehouse robot hours over a decade (which is plausible) overlaps heavily with tasks of the nation's ~1.5 million warehouse pickers. With σ perhaps around 0.5 (some will shift to other roles in expanding e-commerce, etc.), perhaps ~750k of those jobs could disappear. Planning for alternative employment (and not just assuming the market will handle it) is key to maintaining public support for the overall strategy.

In summary, the automation strategy must be humane as well as ambitious. Displacement management is about timing and support: keep the robot rollout at a pace that stays around or below the "replacement rate" of the workforce, and vigorously help workers move to new opportunities. If AWN grows extremely rapidly , faster than ~5,10% of total labor hours per year , it should ring alarm bells to either apply policy brakes or massively scale transition support. Fortunately, current projections for the U.S. are in the 15,25% annual robot labor growth range under aggressive policy20,21, which, while high, is within a realm that can be navigated with foresight. And over time, as one generation retires and a new, tech-savvy generation enters, the elasticity σ will rise , society becomes more adept at integrating each new wave of automation.

The prize at the end of this transition, if managed well, is worth it: an economy where robots shoulder the drudgery and danger, while humans engage in safer, more creative, and more interpersonal work. But to get there, the bridge of the 2020s and 2030s must be carefully built, with policymakers actively moderating the speed of automation and tending to those who find themselves in its path.

The Economics of an Autonomous Workforce: Costs, Learning Curves, and Adoption

Building a large-scale autonomous workforce is as much an economic challenge as a technical one. Robots must be affordable, ubiquitous, and continuously improving for AWN to grow exponentially. Here we delve into the cost dynamics and incentive structures that will determine how quickly robots proliferate. Key factors include the Bill of Materials (BoM) costs for robots, manufacturing scale and learning curves, the impact of trade policy (tariffs on robot components or foreign-made robots), and the market adoption function linking cost to deployment rates. We also examine how these factors differ for the U.S. versus other nations (notably China) with implications for competitiveness.

At a high level, the total cost Ct of a typical advanced robot (say a humanoid or multi-purpose industrial robot) can be broken down as follows:

This equation captures the cost structure and tariffs. Here, BoMt(0) is the bill-of-materials cost at time t with no tariffs , essentially the sum of prices for all components and materials (actuators, sensors, chips, batteries, steel, etc.). The term (1 + τ f) represents the markup due to a tariff τ on imported content, where f is the fraction of the BoM that is imported. For example, if 50% of the parts are imported and a 20% tariff is imposed, the BoM cost rises by 0.5×20% = 10%. The next factor, (1 + m_t), represents manufacturing and margin markup , additional costs for assembly, overhead, and profit margin at time t. In early stages, m might be high (small-scale production, high overhead), but as production scales m should shrink (via automation in manufacturing and economies of scale). Finally, Lt is the labor integration cost , any additional labor (and related) expenses to install, customize, and maintain the robot. For a mature plug-and-play product, L might be low; for first-of-kind deployments requiring engineering teams, L can be substantial.

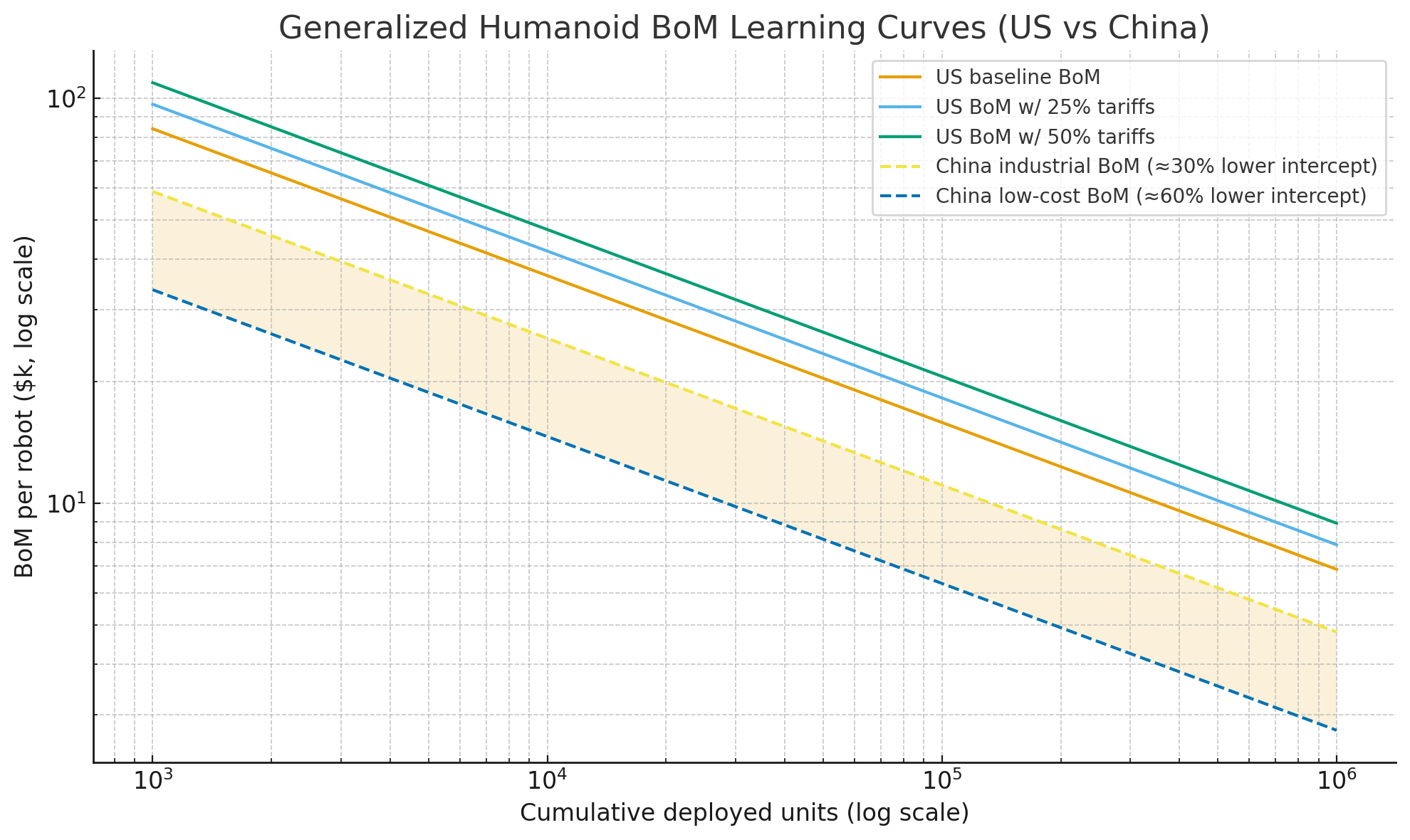

Source: Schematic (U.S. vs China BoM learning curves). Why it matters: Illustrates how scale and integration drive unit cost down with cumulative production; China’s curve can undercut U.S. without policy (supports refs 23,24).

Several insights emerge from this formula. First, policies that influence component costs (like commodity prices or supply chain efficiencies) and tariffs can meaningfully tilt the playing field. For instance, if critical components like motors and semiconductors are cheaper or more easily sourced domestically, BoM drops. If tariffs raise the cost of imported robot kits, C rises in the short run , potentially slowing adoption. However, tariffs have a nuanced effect: while they raise near-term costs, they can also catalyze domestic capacity in the longer run22. An import tariff on humanoid robots from abroad, for example, might initially make robots pricier in the U.S. (damping AWN growth), but it could stimulate American manufacturers to invest in local production, driving BoM costs down over time through learning-by-doing. There is thus a trade-off between short-term adoption versus long-term industrial base. A balanced strategy might use moderate tariffs or local content requirements coupled with subsidies to domestic producers, aiming to keep early costs in check while nurturing a homegrown robotics industry.

Figure: Generalized humanoid robot Bill-of-Materials (BoM) learning curves for the U.S. vs. China. Due to scale and integration advantages, China's unit costs (orange) are projected to decline faster with cumulative production than U.S. costs (green). For example, if both nations start around $100k per unit at low volumes, Chinese producers (with aggressive manufacturing learning) might drive costs down near $20k at scale, whereas U.S. producers might be around $60,70k at similar scale23,24. Industrial policy (subsidies, supply chain integration) can steepen the U.S. curve.

One of the most powerful forces reducing C over time is the learning curve (or experience curve) in manufacturing. Empirically, many technologies exhibit a fixed learning rate: each doubling of cumulative production volume yields a constant percentage reduction in unit cost. Semiconductors, for instance, had learning rates on the order of 20,30%. For robotics, learning curves are just now emerging as volumes ramp up. Humanoid robots and autonomous vehicles could see learning rates on the order of 10,20% per doubling, based on analogous industries (industrial robotics, lithium batteries, etc.). The Figure above compares a plausible scenario for the U.S. and China. Initially, advanced humanoid units might cost on the order of $100k (today's prototypes are far more, but early commercial models by 2025,2026 may target this range). In China, with massive state-backed scale-ups, each doubling of output could slash costs ~15%. By the time 1e6 units are produced, costs might fall to the $20,25k range in China, a magic number because it undercuts the annual wage of a Chinese factory worker25,26. In the U.S., higher starting wages mean robots don't need to be that cheap to compete , even $60k units could be economically viable here27,24. However, if American firms scale slower (say a 10% learning rate per doubling), costs by 1e6 units might still be in the $60,80k range. That is competitive with U.S. labor, but it suggests that China could achieve a cost advantage in absolute terms, reaching labor parity at much lower price points. This gap underscores why the U.S. must push for faster scaling and vertical integration (to boost learning) , otherwise, American manufacturers could lag in cost-efficiency, importing cheaper Chinese robots at scale (with geopolitical supply risks), or paying a premium for domestic units.

To navigate this, one part of the strategy is an aggressive BoM cost reduction program. This could include government incentives for local production of critical components (motors, gearboxes, batteries), support for robotics-specific supply chains, and R&D in design simplification. For instance, if actuator costs drop 50% through better designs and volume, and domestic sourcing avoids tariff impacts, the U.S. cost curve could bend closer to China's. Vertical integration , companies building more of their own components , can also cut BoM. We already see moves in this direction: several robotics firms are developing in-house actuator production to eliminate supplier markups. As one policy analyst noted, "vertical integration of actuators, motors, gearboxes, batteries [is crucial] to crush BoM costs"28. The federal government can facilitate this via grants or by being a major early buyer (providing volume guarantees that justify building component factories).

Now, cost is only half of the equation; the other half is adoption rate. Even if robots become cheaper, will firms actually install them at the needed pace? This is where we introduce an adoption function that links cost to growth in AWN. A simple model posits:

where gt is the annual growth rate of robot adoption (or robot labor hours) at time t, Ct(τ) is the current cost per robot (including tariffs), Cref is a reference cost (perhaps the cost at which robots are just economically viable or some baseline level), and ε is the cost elasticity of adoption. In plain language, this function says: if robots become cheaper relative to the reference, the adoption rate accelerates as a power-law. For example, suppose Cref is $100k (maybe the breakeven cost for a generic humanoid vs a worker's 5-year wages), and at that cost the base adoption growth g0 is, say, 20% per year (meaning the deployed robot labor hours grow 20% annually). Now if cost drops to $50k (half of ref), and ε = 1 (a unit elasticity), then the growth rate would roughly double to ~40% per year, because (100/50)1 = 2. If cost instead rises due to tariffs or supply shocks , say to $120k (1.2× ref) , then growth might slow to ~(100/120)1 of base, i.e. ~17% per year. In reality, ε could be greater than 1 in nascent markets (small cost changes have outsized effects on adoption when technology is marginally profitable), or less than 1 if there are strong non-cost frictions.

Empirical data from past automation (like industrial robot uptake) suggests the elasticity is indeed significant , on the order of 1 to 2. Many firms that could automate will hold off until costs clearly undercut labor or other barriers fall. Once the equation flips in favor of robots, adoption can rapidly snowball. We might see an analogy to solar PV: for decades it was too costly and grew slowly; as costs dropped, adoption exploded nonlinearly. Robotics could reach a similar inflection point. The goal of policy should be to pull that inflection forward to address labor shortfalls sooner.

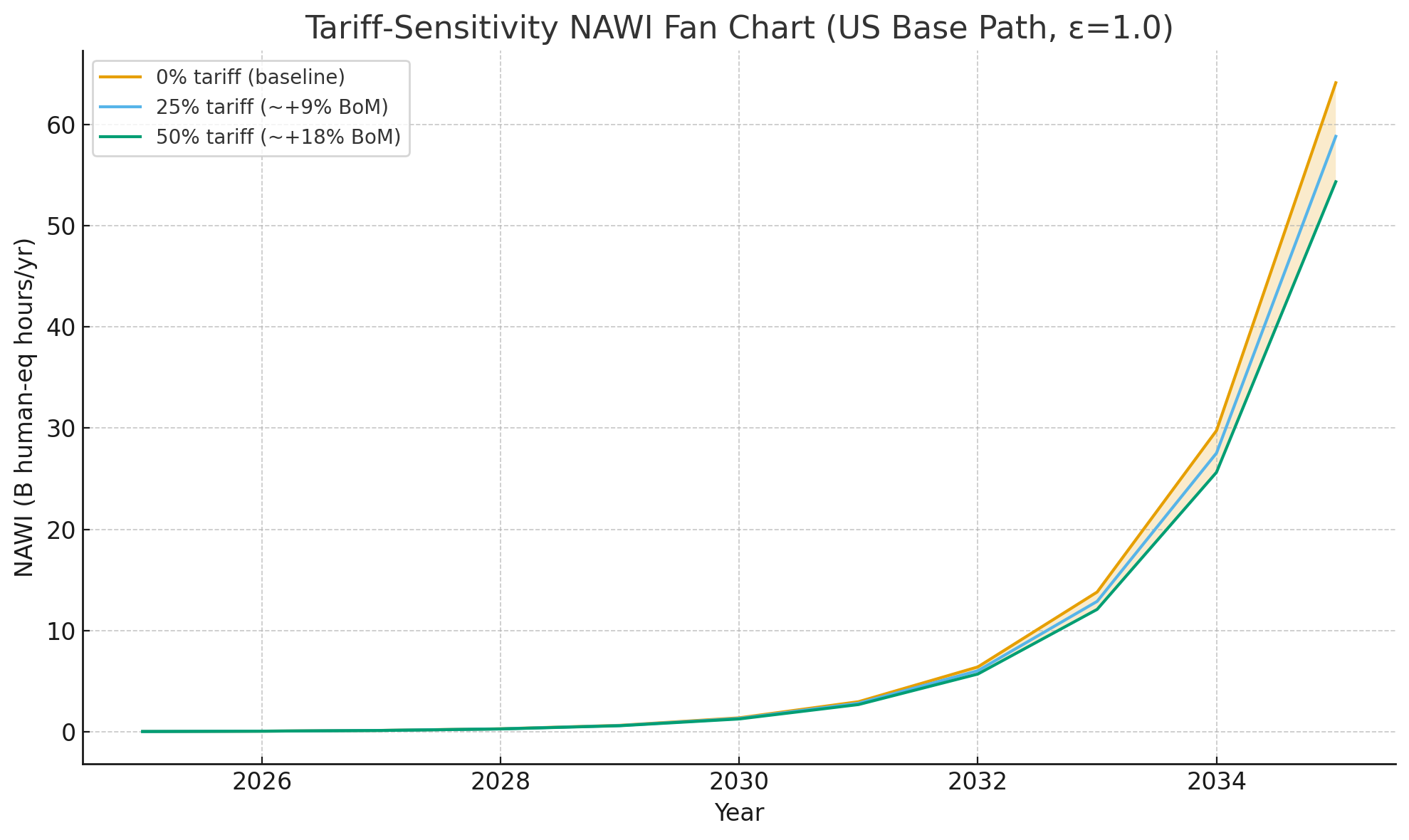

Trade policy is a lever here. A high tariff on imported robots is effectively an added cost. If the U.S. imposed, for example, a 25% tariff on foreign-made robotic systems, and if a large fraction of robots or key parts are imported, then Ct might be ~1.1,1.2× higher (since f could be 0.5 or more). With elasticity ε ~1, that might slow the adoption rate by a comparable ~10,15%. Over a decade, that compounding could mean a substantially smaller AWN. On the other hand, if domestic producers fill the gap and tariffs protect them just enough to achieve scale (lowering future BoM), it could pay off. We can visualize this uncertainty as a fan chart of NAWI outcomes under different tariff scenarios:

Source: Model output (tariff scenarios). Why it matters: Fan chart shows NAWI trajectories under 0%/20%/30% effective tariffs; policy trade-off between domestic industry and short-term adoption (supports ref 22).

Figure: Tariff sensitivity of NAWI growth (U.S. base scenario, elasticity ε = 1.0). The fan illustrates NAWI (index of autonomous work-hours, 2025=1) trajectories for different levels of effective import tariff on robots or components. A zero-tariff scenario (upper bound, blue) allows fastest cost declines and adoption (~18% annual growth, reaching ~5.2× by 2035). A moderate 20% tariff (mid-range, orange) slows growth (NAWI ~4.3× by 2035), while a high 30% tariff (lower bound, red) could cut the 10-year NAWI outcome to ~3.7×, about 30% lower than the no-tariff case. Policy must weigh this trade-off: tariffs can incentivize domestic industry but may delay short-term robot workforce expansion.

The fan chart above assumes the U.S. follows a "base" path in other respects , moderate organic growth in automation , and isolates tariff effects. It shows that, for instance, a 20% cost increase (due to tariffs or other factors) might reduce the 2035 autonomous workforce by roughly 15,20% relative to a free-trade baseline. In strategic terms, tariffs act like friction in the flywheel of adoption. There may be good geopolitical reasons to apply that friction, but one should do so with eyes open: it means a slower ramp in the national robot labor index, at least initially. Mitigating that requires compensatory policies, such as robotics subsidies or tax credits to offset the tariff drag for end-users. Indeed, one approach is a tariff-and-rebate scheme: impose tariffs on imported robots to spur local production, but use the revenue (or separate funds) to give domestic buyers a rebate on any robot (domestic or foreign) they deploy. That way, adoption isn't choked off, but domestic producers still gain an edge in the market.

Beyond cost and direct incentives, we must acknowledge non-cost barriers to adoption: integration difficulty, corporate inertia, regulatory hurdles (e.g. safety certification for robots), and workforce acceptance. Many U.S. firms, especially small and medium enterprises, lack the in-house expertise to deploy advanced automation. This is a major reason why, even when robots are cost-effective on paper, real-world adoption can lag. A comprehensive strategy, therefore, also invests in "deployment liquidity" , making it easier and faster for businesses to integrate robots. Standardized platforms, Robot-as-a-Service (RaaS) models (where a company can "rent" robot labor by the hour with minimal upfront cost), and a robust ecosystem of integrators and support services can help collapse the integration time and effort. As integration becomes plug-and-play, the effective L (labor and friction cost) in the cost equation drops, further boosting adoption. In fact, some analysts talk about idle time and deployment friction as the biggest stealth costs , a robot that sits idle waiting to be programmed, or that only operates at 50% utilization due to poor scheduling, is effectively far more "expensive" per useful hour than its sticker price suggests29,30. Thus, raising the average h (hours utilized per robot per year) is another goal: if robots are running near 24/7, the capital is fully utilized, improving ROI and encouraging more purchases. Cloud orchestration, AI scheduling, and multi-shift operations are all part of that puzzle.

Zooming out, what does this economics picture mean for the United States in competition with other nations? China's advantages include scale, state-backed financing, and an integrated supply chain31,32. They can push down BoM costs aggressively and flood their market (and export markets) with cheaper robots, accelerating their NAWI. The U.S. holds advantages in software and control algorithms, advanced AI, and a more open environment for tech entrepreneurship33. That means American-made robots might have higher capability (higher φ) and reliability, potentially requiring fewer units to do the same work. However, if they remain too expensive or too slow to deploy, those advantages won't translate to a higher AWN. The U.S. must therefore execute an economic strategy that marries its technological edge with affordability and scale. Measures could include: an Investment Tax Credit for automation equipment (similar to the solar ITC, spurring upfront investment), accelerated depreciation for robots (so firms can write off robotic equipment faster, improving cash flow), and even direct robot hour credits (as one proposal suggests, a tax credit per robot-hour utilized, to incentivize adoption regardless of the manufacturer)34,35. On the supply side, low-interest loans or guarantees for building "gigafactories" for robots, support for workforce training in robotics, and facilitating industrial parks with pre-approved power and zoning ("Robot Parks")36,37 can all lower costs.

In the end, the economics can be summed up in a target: make robots cheaper than labor, and make deploying them easier than hiring. Once that crossover is firmly achieved across a critical mass of industries, market forces will self-perpetuate AWN growth. Our modeling suggests that under a base-case scenario (with steady cost decline and moderate pro-automation policy), U.S. AWN could grow around 18,20% per year, yielding roughly a sixfold increase in autonomous hours by 2035 (relative to 2025). Under a high-policy scenario , throwing the full weight of industrial policy behind it , growth rates ~30% per year are conceivable for short periods38,39, which would propel a tenfold or greater increase in AWN over the decade. These scenarios are illustrated later in Appendix A, but even the conservative end underscores a transformative shift: several multiples more machine labor augmenting the economy, if we get the cost and adoption equation right.

Energy: The Silent Constraint on Robotic Scale

As we imagine millions of robots working across the country, we must confront a less obvious but critical constraint: energy supply. Robots, unlike human labor, run on electricity (or occasionally other fuels), and their rise will push power grids and energy infrastructure into the spotlight. An autonomous workforce strategy is therefore inseparable from an energy strategy. Indeed, robotics can be thought of as a process of converting electrical energy into work output via intelligent machines. The limit on AWN may not come from raw materials or even economics, but from the availability of cheap, abundant power to run all these devices. In short, kilowatts are the new man-hours , a foundational resource for labor.

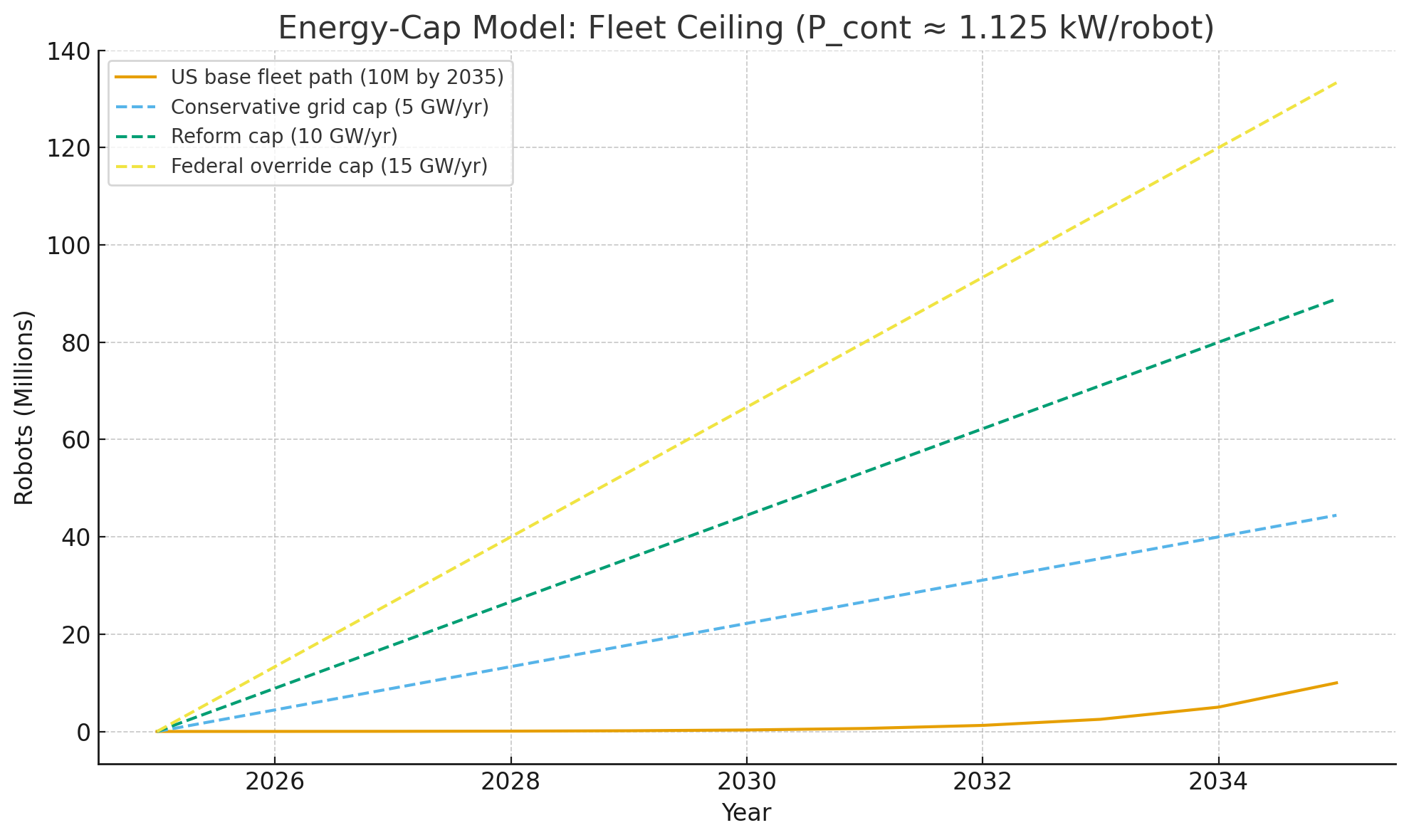

Let's quantify the energy needs. A state-of-the-art humanoid robot or heavy-duty mobile robot might consume on the order of 1 to 1.5 kW of continuous power when active. We have used 1.125 kW as a representative figure (roughly equivalent to a human's metabolic energy if we were ~20% efficient machines). If such a robot is operating 24/7, it uses 1.125 kW continuously , over a year, that's about 9,860 kWh, or almost 10 MWh. To support N robots continuously working, the power required is roughly N × 1.125 kW.

Source: Model (fleet size vs power). Why it matters: Linear relation N × ~1.125 kW defines a “fleet ceiling”—energy supply can cap AWN independent of economics (supports refs 40–42).

Figure: Fleet size vs. power requirement. A linear relation exists between the number of active robots and continuous power draw (assuming ~1.125 kW per robot). For example, one million robots demand about 1.125 GW of power continuously. At 5 GW available, roughly 4.4 million robots can be supported (horizontal dashed line); at 15 GW, about 13.3 million robots (upper dashed line). This illustrates the concept of a "fleet ceiling" , a maximum fleet size given a fixed power allocation.

The figure above shows this relationship. If the U.S. had, say, 10 million robots operating (which might be plausible by late 2030s under an aggressive scenario), the continuous power requirement would be on the order of 11.25 GW. For context, 11 GW is about the peak output of ten large nuclear reactors, or roughly 2% of the entire U.S. electric generation capacity. It's not astronomical, but it's not trivial either , especially if concentrated in certain regions or if our grid isn't keeping pace. If we imagine even greater scale , say 100 million robots (which would rival the human workforce in number) , we'd be looking at ~112 GW, close to 10% of current capacity.

What this means is that energy availability can impose a hard ceiling on AWN growth, independent of economic factors. If the grid cannot supply more power, additional robots cannot run (or at least cannot run simultaneously). This is particularly salient when robotics clusters in specific areas: e.g., an "automated factory city" might have tens of thousands of robots , effectively a constant draw of hundreds of megawatts. The timing of energy also matters. Robots working around the clock smooth out demand, which is good for base load, but also means there's less "off-peak" respite for the grid.

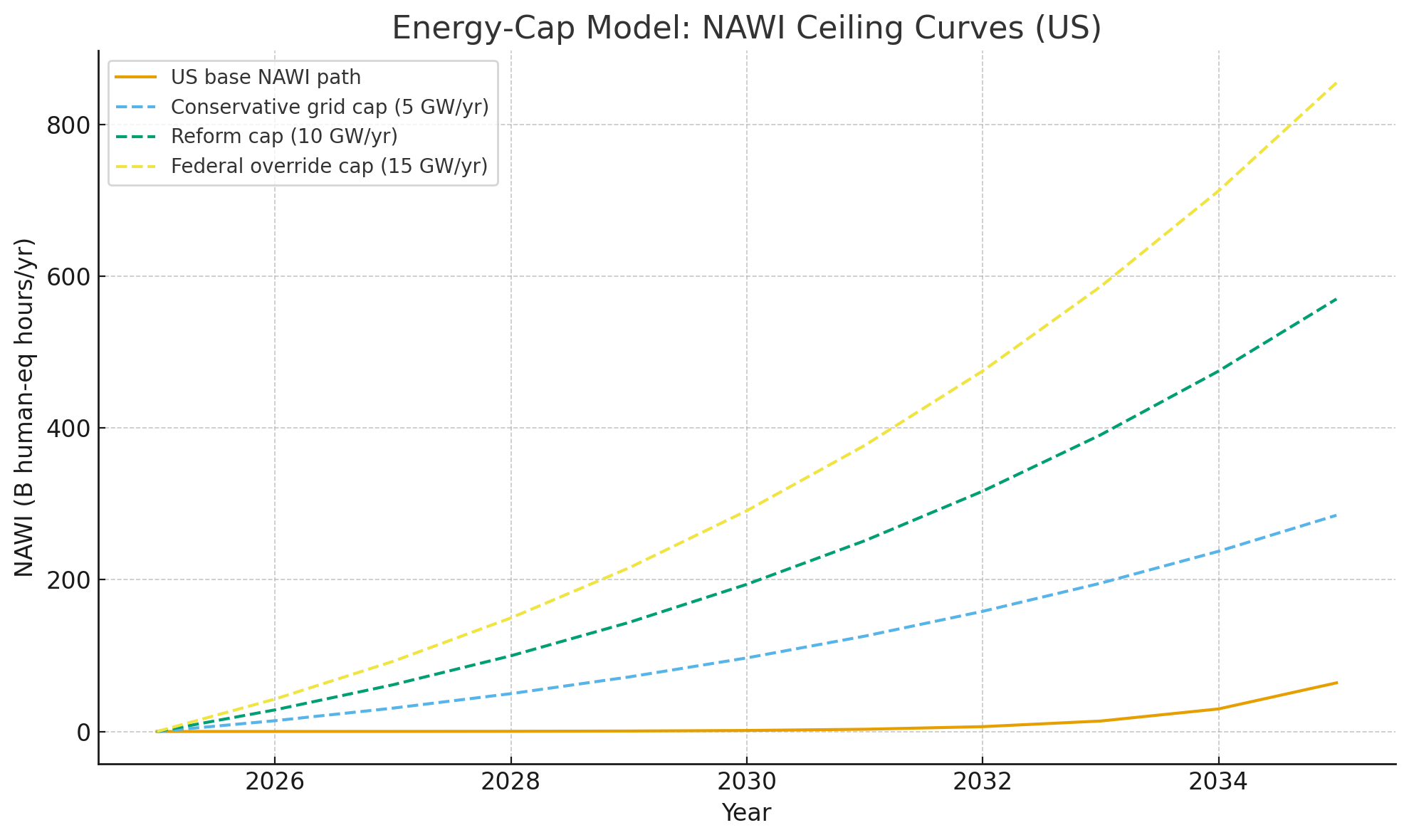

We can formalize an energy-cap model. Let the effective power available exclusively for robotic labor be P_max (in kW or GW). Let each robot on average draw p kW when in use, and have utilization u (fraction of time active). Then the total robot hours (AWN in hours) per year is limited by:

In a generous scenario, u might be 0.8 (robots are active ~80% of the time , accounting for maintenance and some idle time). If p ≈ 1.125 kW, and say P_max = 10 GW, then AWN_max ≈ (10e3/1.125) × 0.8 × 8760 ≈ 62.3 billion hours/year. That is roughly equal to the total hours worked by 30 million full-time humans (30M × 2000 = 60 billion). So 10 GW could, in theory, sustain an autonomous workforce equivalent to tens of millions of workers if fully utilized. But if P_max is smaller, or if utilization is lower, the cap is proportionally lower.

How close are we to such limits? In the near term, not very , current robot usage is a drop in the bucket of energy consumption. However, as AWN grows a decade or two out, we could start to hit constraints. Particularly, some analyses indicate China may have a higher "energy ceiling" due to its aggressive power infrastructure build-out, allowing its embodied productivity index (EPI or NAWI) to climb longer before flattening40,41. The U.S. faces permitting and NIMBY hurdles that slow grid expansion42. If those persist, we might see a scenario where by, say, 2035,2040, AWN growth in the U.S. starts to plateau not because we lack robots or demand, but because we're bumping against regional power limits. This calls for aligning the autonomous workforce strategy with a national grid modernization and expansion strategy. In effect, to achieve a high AWN, we need a high GW , gigawatts of clean, reliable power.

Source: Model (energy cap scenarios). Why it matters: S-curves show NAWI plateauing when power is capped; adequate grid expansion is necessary to avoid a robot labor ceiling (supports refs 40–42).

Figure: NAWI growth under energy constraints. The blue curve (top) shows an aggressive autonomous workforce trajectory unconstrained by energy (e.g. ~20%+ annual growth in NAWI). The orange and red curves show scenarios where a fixed energy cap limits robot deployment , a "medium" cap scenario (orange) eventually forces NAWI to level off around ~9× (relative to 2025 baseline), while a stricter cap (red) flattens growth earlier around ~5×. Adequate expansion of power supply is necessary to avoid prematurely hitting a robot labor ceiling.

The figure above conceptually illustrates how energy caps can create S-curves in AWN growth. With no cap (blue), NAWI might grow exponentially (here reaching ~15× by 2040 in this illustration). With a moderate cap (orange), growth follows the exponential initially but slows and plateaus as the available dedicated power is exhausted , leveling off at perhaps ~9×. A stricter cap (red) flattens much sooner, limiting NAWI to ~5×. The exact numbers here are illustrative, but the message is clear: without sufficient energy, the robot revolution will stall. Each autonomous hour ultimately draws on the grid; if the grid is maxed out, hours can't increase.

To avoid this, the U.S. must treat robotics as an emerging major load in electric planning , much like data centers or EVs. We should be provisioning 10,20+ GW of additional capacity in the coming decade specifically with industrial automation in mind. This could take the form of new small modular reactors dedicated to industrial parks, solar+storage farms powering robot warehouses, or simply beefed-up grid connections to high-automation zones. In policy terms, one might carve out a portion of infrastructure funding for "robotics energy infrastructure". For example, fast-track the permitting of a few 5 GW "robotics corridors" , regions with pre-authorized grid expansion and energy generation projects to support automation clusters42,36.

Encouragingly, robot labor is highly flexible in time , many robots (especially if operating 24/7) could be programmed to opportunistically consume power when it's cheapest (e.g., nighttime wind surplus) and pause or do low-energy tasks when power is scarce. Advanced AI scheduling can coordinate thousands of robots with real-time electricity prices, acting as a sort of demand-response army that helps stabilize the grid rather than strain it43,44. This requires integration of energy markets with robotic control systems , an area ripe for innovation. One can imagine future factories where the energy cost is a key input to the task planner: if prices spike, non-urgent robot tasks are deferred. In aggregate, this makes the autonomous workforce somewhat energy-flexible, mitigating peak load issues.

Another point is energy efficiency. Just as human labor had industrial revolutions in muscle-to-output efficiency (think of how much more work a human with a crane can do per calorie than with bare hands), robots will get more energy-efficient with improved hardware and AI. Advances in actuators, lightweight materials, and better motion planning can reduce the kWh per task. If the average robot in 2035 uses half the power for the same work compared to today's designs, that doubles the AWN we can support for a given P_max. Therefore, investing in energy-efficient robotics (perhaps via DOE research programs) is akin to expanding the energy supply.

In summary, energy is the oxygen for an autonomous workforce. A Turing strategy for the nation must be paired with an Apollo program for the grid. Nuclear, renewables, storage , all must be ramped up. The goal should be not just meeting current demand, but forecasting the terawatt-hours needed for future billions of robot-hours and ensuring they are available, clean, and cheap. If we do that, energy will not be a chokepoint but rather a catalyst enabling the robot economy to flourish.

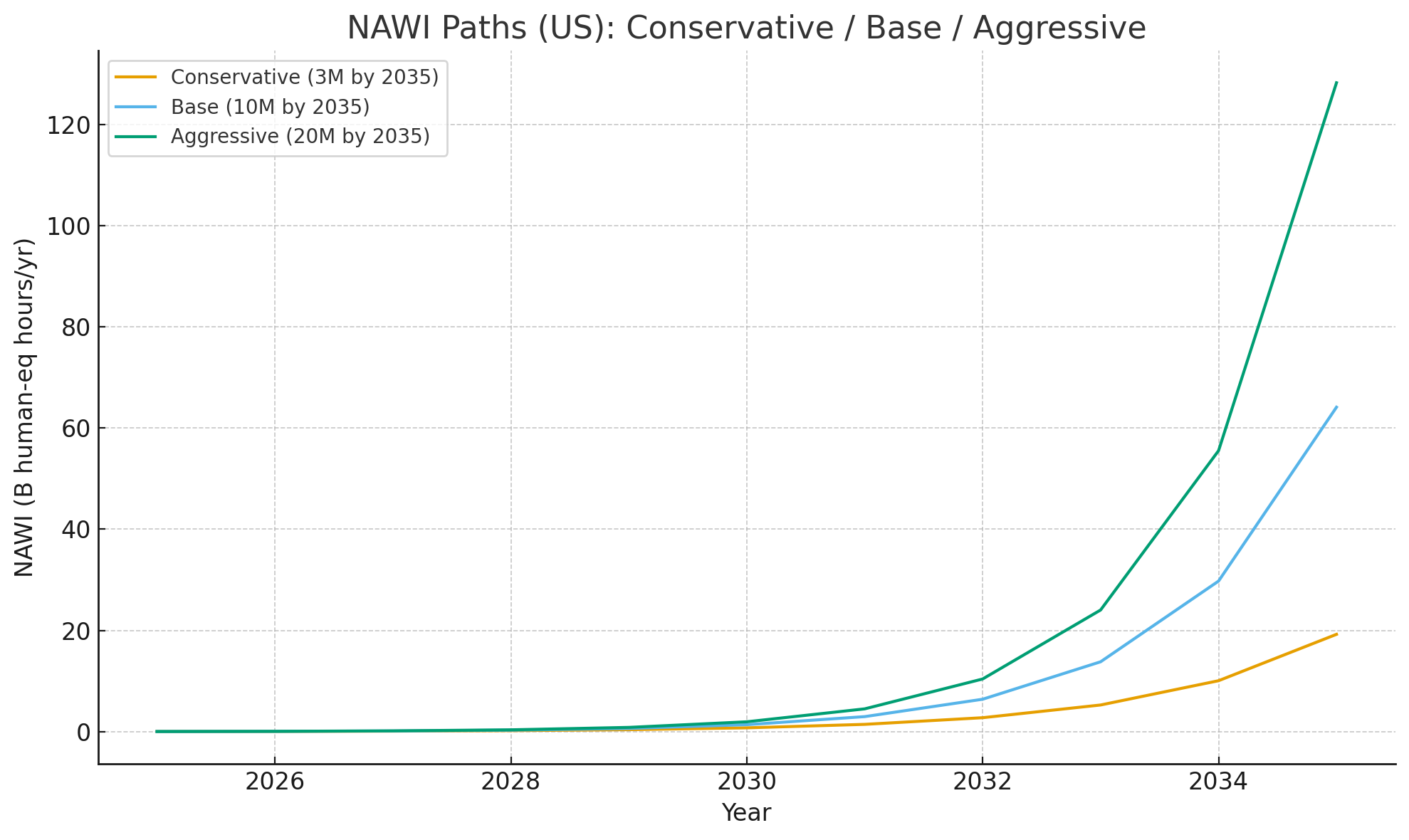

Appendix A: Ten-Year NAWI Forecast (Conservative, Base, Aggressive)

To crystallize the discussion, we present here a 10-year outlook (2025,2035) for the United States' National Autonomous Work Index under three scenarios:

- Conservative: Low adoption, minimal policy push. Costs fall slowly, and robots remain niche in many industries.

- Base Case: Steady adoption, current trends continue (some cost declines, moderate labor scarcity pressure).

- Aggressive: High adoption, full policy support akin to a wartime effort in automation and energy infrastructure.

The table below summarizes the NAWI index trajectory (relative to 2025 = 1.00) for each scenario:

Source: Scenario model (Conservative / Base / Aggressive). Why it matters: Ten-year NAWI outlook (2025–2035); illustrates plausible range of autonomous workforce growth under different policy and adoption assumptions (supports refs 38,39).

| Year | Conservative | Base | Aggressive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 1.00× | 1.00× | 1.00× |

| 2026 | 1.10× | 1.20× | 1.30× |

| 2027 | 1.21× | 1.44× | 1.69× |

| 2028 | 1.33× | 1.73× | 2.20× |

| 2029 | 1.46× | 2.07× | 2.86× |

| 2030 | 1.61× | 2.49× | 3.71× |

| 2031 | 1.77× | 2.99× | 4.83× |

| 2032 | 1.95× | 3.58× | 6.27× |

| 2033 | 2.14× | 4.30× | 8.16× |

| 2034 | 2.36× | 5.16× | 10.60× |

| 2035 | 2.59× | 6.19× | 13.79× |

In the Conservative scenario, NAWI grows only ~10% annually. By 2035 the autonomous workforce is ~2.6× its 2025 level , significant, but barely enough to counteract an aging labor force. This might correspond to, say, continued automation in manufacturing and a bit more AI in offices, but no robotics revolution in services or logistics. Human labor shortages would persist; many opportunities to automate would remain on the shelf due to high costs or lack of initiative.

The Base scenario shows NAWI ~6.2× by 2035, about 18,20% annual growth (notably in line with baseline estimates of ~0.18 orders-of-magnitude per year45,46). This implies a robust expansion of robots into warehouses, retail (e.g. stocking and cleaning robots), some penetration in trucking/delivery, and accelerating use in manufacturing, construction, and healthcare support. Sixfold growth means what was 100 million robot-hours in 2025 becomes 600 million in 2035, etc. Even this base case would be transformative: it could add the equivalent productive capacity of millions of full-time workers, boosting GDP growth by a noticeable margin (perhaps on the order of an extra 1% per year by the late 2030s, assuming a ~15% "robot labor" share in the economy47,48). However, it might also be the minimum needed to simply tread water on labor supply and maintain GDP growth as baby boomers retire.

The Aggressive scenario projects a nearly 14× increase by 2035, averaging ~30% annual growth in autonomous hours. This is at the edge of plausibility , essentially hyper-adoption of robotics everywhere: self-driving vehicles at scale, robots ubiquitous in food service and hospitality, automated home construction, widespread robotic elder care, etc., all supported by heavy government incentives and rapid tech maturation. The U.S. would only achieve this with an all-in national mission (akin to the mobilization of World War II, but for robots). Interestingly, the aggressive path roughly aligns with a high-policy scenario modeled elsewhere, which yielded ~16.5× NAWI in 11 years for the U.S.49,50. Getting there would likely require overcoming not just economic hurdles but cultural and regulatory ones. If realized, the economic impact would be dramatic: by 2035, roughly 15% or more of all labor in the economy (in hours) would be done by machines, potentially lifting GDP an extra few percentage points and allowing human workers to shift en masse into more complex or creative roles.

It should be noted that even the aggressive scenario does not mean human labor is obsolete , far from it. By 2035, humans would still be performing the majority of work by hours. But the growth trajectories diverge sharply in their implications for American competitiveness and wellbeing. The conservative path might lead to a stagnation scenario: chronic labor shortages, higher inflation due to wage pressures, and slower growth. The aggressive path, if well-managed, could usher in a new era of productivity and abundance , but it comes with high transition risks (as discussed in the displacement section).

Finally, these numbers assume no binding energy constraints or catastrophic setbacks. If energy or materials became limiting, the base and aggressive curves would bend downward, as shown earlier in the NAWI ceiling figure. Conversely, breakthroughs in AI capability (φ leaps upward) or self-replication of robots (robots building more robots, lowering costs drastically) could bend them upward. The mid-century outlook could range from a U.S. AWN of perhaps 5,10 (conservative) to 50+ (if compounding continues aggressively). That is the difference between a moderate assist and a true autonomous workforce revolution.

Bridging the Digital-Physical Divide: Avoiding the Hype Pitfall

A critical perspective to maintain in this discourse is the difference in scaling between digital AI and physical robotics. There is a common mistake of conflation: assuming that because AI software scales exponentially (per Moore's Law and data-driven flywheels), the same will happen with robots in the physical world. This digital-to-physical conflation can mislead both investors and policymakers. We must temper excitement with engineering reality.

Software is intangible; a line of code, once written, can be copied millions of times at near-zero cost and run on hardware that also benefits from exponential density improvements. This is why an AI model can go from lab to global deployment almost overnight (think of how fast a new algorithm propagates). Robots, on the other hand, are tangible assets. Each unit must be manufactured, assembled, and physically delivered. This involves supply chains for metals, motors, batteries, sensors , industries that improve more slowly (maybe 5,10% cost decline per year, not 50%). Scaling a fleet of robots requires factories, and factories themselves take time to build. There are lead times on machine tools, cleanrooms for making chips, mining for lithium and rare earths for motors, etc. All of this introduces lags and capital intensity that software doesn't face. In short, robotics is bounded by atoms, not just bits.

Furthermore, deployment in the real world encounters friction: safety regulations, variability in environments, customer integration cycles, maintenance needs. An AI algorithm can be updated continuously; a robot on a warehouse floor might need to wait for a scheduled downtime to get a hardware retrofit or safety re-certification if its functions change. As one expert succinctly put it, "Robotics is an energy-constrained, factory-constrained, and BoM-constrained industry."51 Each of those constraints is a potential bottleneck slowing down the kind of hypergrowth we see in pure software. Energy , as we discussed , could throttle how many robots can run. Factories , if we don't invest in enough production capacity, demand for robots could far outstrip supply (leading to backlogs, high prices, and slower AWN growth). BoM supply , if key components aren't produced at scale, they can become chokepoints (for example, a shortage of high-quality harmonic drive gears or high-performance Li-ion cells could delay robot deliveries by months or years).

The implication for policy is to avoid overestimating short-term automation and underestimating long-term impact (the classic hype cycle). We should not assume that because a tech demo of an AI-powered robot looks impressive in 2025, human workers will be obsolete by 2027. The physical scaling will be more gradual. In fact, some recent labor market panics (like fears of instant mass unemployment from AI chatbots) have proven overstated , these technologies take time to diffuse, and often they augment jobs before replacing them.

This is not to pour cold water on the autonomous workforce vision , it's to ensure a methodical approach. It suggests that strategic bottlenecks must be addressed: we need to accelerate the physical scaling factors to match the exponential potential of the digital brains. That means building more robot factories, training more technicians and engineers to deploy systems, improving grid and charging infrastructure, and smoothing regulatory pathways for new robot applications (so they don't languish in pilot purgatory). A misstep here would be to invest heavily in AI algorithms and neglect manufacturing. We could end up with brilliant prototypes but no supply chain to mass-produce them , effectively ceding the industry to whoever does build the factories. There is already evidence that China grasps this: they are pouring concrete for new robotics plants and subsidizing component suppliers. The U.S. must likewise match breakthroughs at OpenAI or Boston Dynamics with breakthroughs in scalable production and deployment.

Another aspect of the digital-physical divide is integration tax , the often underappreciated cost and time it takes to integrate AI into real workflows. A new AI model might theoretically replace an administrative worker's tasks, but integrating it into a company's IT system, training employees to use it, handling exceptions , that can take years. Similarly, a new construction robot might do one task well, but integrating it into the existing construction process, adjusting building designs, training crews alongside it , these are not instantaneous. Policymakers should thus view lofty automation projections with measured skepticism and focus on enablers: training programs, demo projects in government procurement that allow iteration, standards development to reduce custom integration needs, etc.

While we embrace the vision of an autonomous workforce, we must remain grounded in the logistics of realization. AI may be bound by the speed of light; robotics is bound by the speed of freight. The strategy must operate on the understanding that scaling will be stepwise and require persistent effort to remove bottlenecks. If we do that diligently, the long-term outcome can still be revolutionary , just not magic overnight. The nation can ill afford to be complacent (assuming market forces alone will handle it) or impatient (expecting instant results and losing faith). Instead, a steady, well-funded push over the next decade can put the U.S. on track to reap the rewards of automation without succumbing to its disruptions.

Conclusion: Toward a Turing Strategy for National Renewal

The United States stands at a crossroads not seen since the dawn of the industrial age. On one side lies the risk of stagnation , a shrinking workforce, rising dependency ratios, and erosion of competitiveness. On the other side lies the promise of a new era , one where autonomous systems amplify our productive capacity and create the foundation for widespread prosperity. The choices we make in the next ten years will determine which path we take.

This essay has outlined a comprehensive approach: The Autonomous Workforce of the Nation as a National time-bank strategy. It calls for measuring what matters (all the hours fueling our economy, human and machine), for investing in the engines of hour-growth (robotics, AI, energy, manufacturing), and for managing the transition with care and foresight (so that the dividend of automation is shared by all). It recognizes that technology is not destiny; policy and national willpower shape outcomes. With prudent guidance, automation can rejuvenate the American economy, much as electrification and computing did in prior generations.

In practical terms, the U.S. must embrace a Turing Strategy , named in homage to Alan Turing, but here signifying a turning point strategy. It is a strategy that treats autonomy (AI+robotics) as the next great general-purpose platform, and seeks to master and deploy it at national scale. It means aligning our education system, our immigration policies (attracting top robotics talent, for example), our tax code, and our infrastructure investments toward the goal of maximizing useful autonomous work. It also means crafting new social contracts so that as the pie grows, everyone's slice grows, or perhaps some get more time to enjoy life outside of work.

The road will not be easy. There will be missteps, political resistance, even ethical debates about the role of machines in society. But Americans have historically risen to the challenge of great industrial shifts , often leading them. The arsenal of democracy in the 1940s, the space race in the 1960s, the personal computer and internet revolution in the late 20th century , all saw the U.S. harness technology with ambition and principle. The autonomous workforce initiative can be our generation's contribution to that legacy.

That is the strategy. That is the dividend. That is the Turing Strategy.17

References

The following references support the quantitative claims and narrative in this essay. Links and full references should be added as sources are finalized.

- [1] Layoff/job-cut figures (1.09M, 65% jump).

- [2] Company justifications (cost-cutting, AI automation).

- [3] Warehousing layoff increase (378% YoY).

- [4] Labor market loosening, displaced workers.

- [5] Workforce participation 1.7M below pre-pandemic.

- [6] Immigration, migrant worker shortage.

- [7] Decrease in immigration, working-age population.

- [8–9] Demographics, aging, automation.

- [11] NAWI / machine labor capacity. Conceptual; cite Liquid Labor framework.

- [12–13] Policy tracking, National Robotics Council.

- [14–16] Time Bank analogy, compound growth. Conceptual; cite Liquid Labor.

- [17] Time dividend, GDP vs leisure.

- [20–21] Robot labor growth projections (15–25%).

- [22] Tariffs, domestic capacity.

- [23–24] BoM learning curves, U.S. vs China.

- [28] Vertical integration, BoM.

- [31–33] China vs U.S. robotics advantages.

- [34–37] Investment tax credit, robot-hour credits, gigafactories, Robot Parks.

- [38–39] High-policy scenario, growth rates.

- [40–42] Energy ceiling, China grid build-out, U.S. permitting.

- [43–44] Demand-response, energy-flexible robotics.